Keeping A Good Game Down

One-pocket is one of the most acquired of tastes. An intense, cerebral contest, it is closer in spirit to chess than to pool. When watched and appreciated by knowledgeable fans, it is one of the most exciting and satisfying of cue games. Unfortunately, most spectators get fed up and leave when no one sinks a ball for 20 minutes. So this beautiful game is doomed to have much the same crowd appeal as curling — a small group of enthusiastic railbirds amidst an audience of largely confused patrons wondering what all the fuss is about.

And on top of that the game is highly regional. Growing up in New York in the 1960s, I never saw a rack of one-pocket. The Apple was a straight-pool town, and in that game the idea is to sink balls, not huddle them near the mouth of pocket. But in present-day Philadelphia, 90 highway miles to the south, the serious money game is one-pocket, and of an afternoon you don’t have to try too many rooms to see thousand-a-rack action if that’s what you’re looking for. Of course the pace of the game is slow enough that at that price playing is not much more expensive than hiring a lawyer, but a lot more fun.

My first real exposure to it came at Bananas in San Antonio, a classic oasis owned by Frank “Bananas” Rodriguez, who seemingly draws one-pocket players from as far away as Neptune. I sat mesmerized though one 45-minute battle after another, downing Dos Equis with each one. You can sell a lot of beer to one-pocket fans since they sit so long in one place that liquid relief becomes an imperative.

Ask a casual player which of the following games is the oldest: nine-ball, straight pool, eight-ball, or one-pocket, and you stand to win a bet. Though I listed them in order with the youngest first, most people guess that one-pocket is the junior game since it only came into tournament prominence after 1960.

But the origins of one-pocket date to the late 1700s, long before the cue tip was introduced. Since billiards was a gambling game, from the earliest times methods had to be developed for handicapping, to equalize the differences in skills between players to create a fair game. A contest in which one or both players was restricted in some way from making certain shots was called a “cramp game,” since the player was “cramped,” or not given free rein to play arbitrary shots.

One way to cramp was to forbid a player from sinking balls in a specific pocket. This earliest ancestor of one-pocket was called the “Bar-Hole Game,” since one of the six holes was “barred” to the player. The first rules for it were published in 1775 in the Annals of Gaming. This is a very rare work, but a microfilm copy can be found in the New York Public Library. The game is mentioned briefly in E. White’s Practical Treatise on the Game of Billiards from 1807. Copies of this book are plentiful and it has become a favorite among billiard collectors (Fig. 1).

White goes on to describe a game called One-Hole, which is eerily similar to modern one-pocket: “In this game, all balls reckon which go into one hole. The player at it, although he seems, to those unacquainted with the game, to have the worst, has in fact the best of it; for as all balls which go into the one hole reckon, the player endeavours to lay his ball constantly before that hole, and his antagonist frequently find it very difficult to keep one or the other ball out, particularly at the leads [the break=””][/the].” White was talking about a situation in which one player (supposedly the stronger) got credit for all balls that went into one specific pocket, while the other player (ostensibly the weaker) got credit for all balls that went into any of the other five pockets. This would seem to give a great advantage to the weaker player, but as White points out it does not. With only three balls on the table, the stronger player keeps maneuvering object balls toward his own pocket so that even though the other player has five pockets to work with it does him no good.

several one-pocket variations.

By the time of Captain Crawley’s The Billiard Book in 1866, the game was known in many variations (Fig. 2). The original One-Hole game was now called One Pocket to Five, and there was also Two Pockets to Four. A third form, said to be interesting when played by shooters of equal skill, was Side Against Side, in which each player gets the three pockets on opposite sides of the table. “Captain Crawley” was the pseudonym of George Frederick Pardon (1824-1882). He took the name from the Captain Crawley character in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847-48), who is an all-around gamester and is mentioned several times in connection with billiards. On one occasion, he relieves a Mr. Kean of a fair quantity of cash: “His [Kean’s][/Kean’s] hotel bill, losses at billiards and cards to Captain Crawley had almost drained the young man’s purse, which wanted replenishing before he set out on his travels.” Pardon wrote books on billiards, chess, backgammon, draughts (checkers) and a host of card games. One of the editions of his Billiard Book contains a thorough bibliography of billiard books published in English before 1877, a very valuable resource.

Harper’s Weekly, March 31, 1866.

The earliest use of the actual term “one-pocket” alone I can find is in the 1869 Roberts on Billiards, by John Roberts (Fig. 3). He says, “This was Kentfield’s strongest game, and he really knew it very well. The more skillful player usually takes the top left [foot][/foot] pocket, and his object is to keep doubling [banking][/banking] the red ball as near to it as possible, because every time his adversary makes a hazard into that pocket, it scores against him. On the other hand, if the better player makes a hazard into any of his opponent’s pockets, the score counts against him.” This is certain an apt description of a common one-pocket move, to repeatedly bank a ball away from an opponent’s pocket toward your own.

Jonathan Kentfield was the first acknowledged billiard champion of England. He wrote the first prominent instructional book following the introduction of the cue tip, and was a master player at several styles of the game. The fact that he was expert at one-pocket suggests that because of his skill he was often obliged to give a handicap to other players. The object of that exercise, of course, is to appear to give a substantial spot when in fact the advantage may be negligible or non-existent.

John Roberts, Sr. was English champion from 1849 until 1870. His son, John Roberts, Jr., followed the family tradition and was world English billiards champion many times during the 1870s and 80s. The son was fond of challenging players in other countries at their own game. He lost to Alfredo De Oro at pocket billiards in one such contest. Frank Ives turned the tables on Roberts by challenging him to English Billiards, Roberts’ own game, and Ives beat him. Roberts Sr.’s 1869 book is notable for a 60-page chapter on hustling called “Sharp Practitioners” and a 90-page chapter on “Celebrated Matches,” taken from actual newspaper accounts going back to 1850.

For much of its early history, the Billiard Congress of America was very conservative in its approach to official rules. It did not deign to publish rules for what were regarded mainly as gambling games, for fear of perpetuating negative stereotypes. Thus it was that the massively popular game of nine-ball, which had been played extensively since the 1920s and was a major component of the 1961 film The Hustler, was not even mentioned in the BCA Rule Book until 1967.

A little-noticed feature of that 1967 edition was the inclusion of one-pocket, also for the first time. The rules were, at merely half a page in length, horribly incomplete (Fig. 4). This was remedied somewhat in a general rules cleanup in 1980, which resulted in 40 pages of rules being added to the BCA Rule Book, and there has been no significant change to the official rules since then. (In an early example of political (in)correctness, the game was known as “One Pocket Billiards,” but the 1980 revision changed it to just “One Pocket.”)

A game played with only three balls is quite different from modern one-pocket, which is played with all 15 object balls. Diligent research has failed to turn up any printed rules for the full-rack form prior to 1967, which means the one-pocket tradition must have been completely oral.

As with nine-ball, one-pocket thrived as a gambling contest, not as a tournament game. Therefore the documentary history of these games is very spotty. We still don’t know, for example, how or when nine-ball developed. Most of the information we have is anecdotal. A player reminisces and is quoted as saying, “I learned one-pocket from X and he was taught by Y, who was the best player in Arkansas in the 1940s,” and so forth. While these tales are entertaining, it is difficult to piece together from them a coherent and reliable sequence of events that would satisfy a historian. And hearing the same story from ten different sources does not increase its trustworthiness, since the sources may all have heard the narrative from the same person.

Normally a billiard historian would look around for the first appearance of a game’s printed rules. In the case of one-pocket we already know that — the interesting question is what caused the rules to disappear and not surface again until 1967, despite rampant evidence that the game was popular at least as far back as the 1930s. After a flurry of variations from 1775 until 1877 (the second edition of Crawley’s Billiard Book), no book seems to have contained any one-pocket rules until 1967, and that includes all official rule manuals there ever were. We have a total void for 90 years. Even Phelan never mentioned the game. How to explain this?

There has long been a feeling that gambling gives pool a bad name, and that if anyone connected with the game ever admitted that an occasional bet is placed on the outcome of a rack, the earth would open up and swallow all of us. The Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, which controlled billiards with a vise-like grip from 1875 until 1960, carefully managed this image. What was bad for billiards was bad for Brunswick, so the company saw to it that nothing ever happened that was bad forbilliards. It sponsored the tournaments, invited the participants, made the rules, published the rule books and paid the bills of the sanctioning organizations. If Brunswick didn’t want one-pocket to exist, it didn’t exist — at least there was no printed evidence that it did. The period of Brunswick’s dominance coincides remarkably closely with the absence of one-pocket (and nine-ball) from tournaments and rule books.

In 1960, Brunswick diversified and became a conglomerate. It gave up control of billiards, which made it possible for tournaments like the Johnston City hustlers’ events to take place. Before 1960, anyone who played in a “hustler’s” tournament would never be invited to participate in a world championship. In those days, there was very little organized pocket competition, usually confined to an annual tournament and a small number of challenge matches. Being ostracized from this small circle of events would have been fatal to one’s career.

It’s no coincidence that the Johnston City tournaments, which made one-pocket famous, started in 1961. Soon after, the BCA moved from Toledo to Chicago and change the composition of its rules committee to include Willie Mosconi, Irving Crane, Joe Balsis and Don Tozer (among others), all of whom were tournament players who grew up knowing and watching one-pocket. No doubt their opinion was influential in adding that game and nine-ball to the rules.

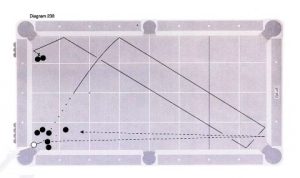

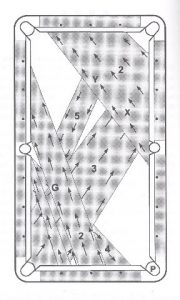

Once a game is official, it gains respect, and people want to learn how to play it. But there the world was stymied. Despite a long history of printed rules, there was a total absence of any instruction on game strategy or technique for one-pocket in any language. This bizarre situation persisted until 1993, when Eddie Robin, former U.S. three-cushion champion, published Winning One-Pocket, based on contributions from a large number of great players (Fig. 5). The only other treatment of the game in any detail is Jack Koehler’s Upscale One-Pocket, which followed in 1995 (Fig. 6). Koehler goes into great detail on banking, including round-the table banks. These shots are usually not attempted in other games, since failure to make them leaves the opponent with an easy shot. This is not so in one-pocket, which therefore requires special skills not used in other disciplines. Robin’s second book on the subject, Shots, Moves and Strategies, appeared in 1996. But one-pocket deserves a shelf of books, not just three volumes, so I hope many other writers will add their own insights to literature of this remarkable game.

Copyright 2002 Mike Shamos

Mike Shamos is Curator of The Billiard Archive, a non-profit foundation set up to preserve billiard history. The reprint of this article is with permission. This article appeared originally in Billiard Digest.